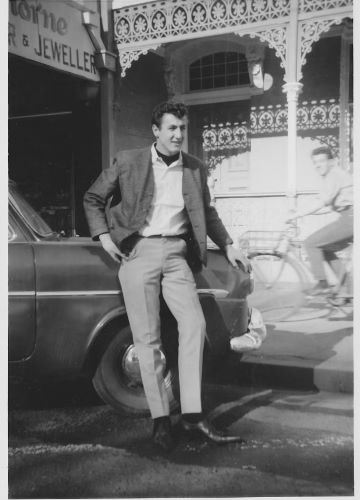

My father Lindsay Fry passed away suddenly eight months ago. He had end stage cancer, which was found well advanced on his lung and spine.

By Craig Fry

Adjunct Associate Professor of Public Health

Victoria University

Introduction

My father Lindsay Fry passed away suddenly eight months ago. He had end stage cancer, which was found well advanced on his lung and spine. Sadly, my father died just seven weeks after his diagnosis. He was two weeks short of his 70th birthday.

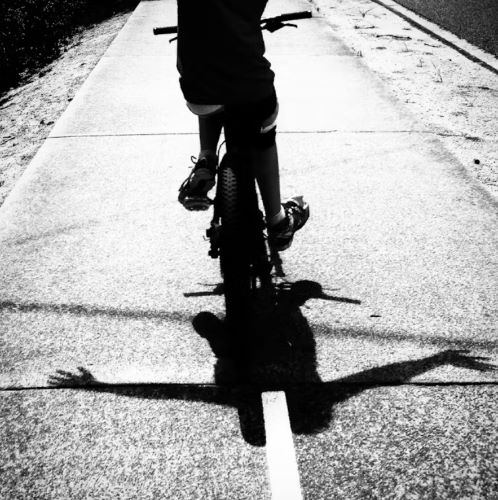

I was not prepared at all for my father’s death. It was a great shock, and the resulting grief floored me. The people around me seemed under prepared too – the daily conversations at work, around the dinner table, with family, and even out riding bikes with friends didn’t often accommodate deeper dialogue around the bereavement experience.

It is a difficult topic after all … death. Most people simply don’t want to follow you too far down that road. Men especially, it seems, are not great at discussing death and grief. An expert in the field suggested to me that this is partly because many men are ‘instrumental grievers’ – we seek active practical outlets for processing grief.

That was certainly me. In the depths of grief, I didn’t always possess the words to describe and understand what I was feeling. But I was lucky enough to discover quickly that cycling helped me.

I was so struck by this that I decided to write about it – the resulting book, Ride: A memoir to my father, was published this week. It’s a personal account of loss and grief, and how the simple act of riding a bike through familiar roads and places has kept me (mostly) sane and well.

I’m no academic expert in this area, but I found that writing a book about my own grief experience made me wonder more about the role of the humble bicycle when it comes to life’s inevitable mental health and wellbeing challenges.

I decided to look into this further. Here’s what I found.

Exercise and Mental Health

While there is a large amount of academic literature on the mental health benefits of exercise generally, the science here is not clear cut. For instance, a 2013 systematic review of the effects of exercise on depression concluded effect sizes are moderate at best, and of uncertain duration after exercise stops. In contrast, a 2016 meta-analysis of 25 randomised controlled trials of exercise interventions reported large significant antidepressant effects in people with depression (including major depressive disorders).

A common conclusion made in some of the best designed twin and review studies is that while regular exercise is associated with reduced anxiety and depressive symptoms, that relationship is not causal. This means the observed positive mental health effects are complex, and involve a range of other individual and environmental factors besides exercise.

Overall, the evidence seems to suggest that the potential mental health benefit from exercise is not something that all people will necessarily experience. Observed effects can vary as a function of illness severity, study group exercise experience (untrained, recreational, elite), exercise type (frequency, intensity, duration etc), and the chosen measure of mental health. For some of the most severe forms of clinical depression exercise alone is unlikely to be the entire answer.

Cycling and Mental Health

Far fewer studies have focused on the mental health benefits of cycling specifically. However, similar findings can be found to those for other exercise. For example, a 2004 Polish review study reported that improvements in depressive and other mood disorders are greatest for rhythmic aerobic exercises like cycling.

A 2007 Cycling England review report concluded that:

[…] cycling has a positive affect on emotional health – improving levels of well-being, self-confidence and tolerance to stress while reducing tiredness, difficulties with sleep and a range of medical symptoms.

And 2011 pilot work in Sydney trialling a bicycle program for mental health service users showed promising results with self-reported mental and physical health improvements for participants.

Outside of the academic literature, there are frequent claims about the benefits of cycling for mental health, including popular articles on how cycling can make you smarter and happier. There has been a published guide to depression for cyclists, and Victoria’s Department of Health & Human Services currently provides this public advice on cycling and mental illness:

Mental health conditions such as depression, stress and anxiety can be reduced by regular bike riding. This is due to the effects of the exercise itself and because of the enjoyment that riding a bike can bring.

Claims about the mental health benefits of cycling can be observed at a number of levels, including elite and amateur competitive cycling, for recreational riders, and for people new to bike riding.

And in recent times a number of high profile people have commented publicly about the positive power of cycling in this area – for example, former Australian Rugby professional Mat Rogers recently argued:

I think that blokes in a cycling bunch would be the least depressed of any group of men because they get stuff off their chest, they talk, and they don’t feel like they’re getting looked down on or judged.

Indeed, as one journalist put it recently:

[…] the anecdotal evidence from recreational cyclists and bloggers is overwhelmingly in favour of the beneficial effects of getting out on your bike and riding the black dog off your wheel.

What is it About Cycling?

On the question of why physical activity and exercise like cycling has been associated with positive mental health outcomes, the academic literature has pointed to both physiological mechanisms (e.g. the thermogenic, endorphin, and monoamine hypotheses) and psychological mechanisms (e.g. improvement of self-efficacy, distraction, and cognitive dissonance).

Popular accounts have also emphasised social psychology principles to explain the apparent connection between cycling and wellbeing, with one Australian psychologist observing recently:

Cycling seems to possess an array of attributes that boost happiness in ways that few other sports can claim…Cycling boosts mental health.

But again, while it appears there are potential mental health benefits to be had from cycling, this doesn’t mean the bicycle will be a panacea for all our mental health ills. On the contrary, there have been some suggestions of negative mental health impacts at the highest levels of competition cycling, for example:

- There may be unexpected negative mental health side-effects in competition cycling due to things like the stress of training and other preparation, performance anxiety when racing, and other stressors for elite competitive cyclists especially.

- Some writers have discussed the possible links between depression and doping in professional cycling.

There has also been the suggestion that certain personality types more vulnerable to mental health problems may be more prevalent in elite cycling. For instance, former world hour record holder and world champion cyclist, Graeme Obree, has said this about depression and cycling:

A lot of people who suffer from depression have a tendency to have obsessive behaviour – that’s why more of them exist in the top end of sport. The sport is actually a self-medicating process of survival.

Cycling and Grief

Much less has been written in the academic literature about how exercise and physical activity like cycling might help people when grieving the loss of a loved one – although some experts like the Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement suggest that exercise can be one useful coping strategy along with others.

Most of the available sources on this question are from personal anecdotes. There have been some books on the topic, such as the recent anthology Cycletherapy: Grief and Healing on Two Wheels and Matt Seaton’s 2002 The Escape Artist. There are also blog articles where the recurring theme is that the bicycle can indeed help in grieving, as these examples show:

In the days before his seventeenth birthday, Tolstoy’s adored son Vanechka had died of scarlet fever. It hit him as hard as his brother Nikolay’s death in 1860, and Tolstoy saw cycling as a kind of “innocent holy foolishness” that allowed him to deal with his grief. (TolstoyTherapy)

There is no instruction manual for grief – you have to find your own path through it. For us that involves a lot of biking. Biking has been our form of therapy. It has kept us living in the present, brought us joy, kept us healthy and reconnected us to the world. (AxelProject)

I had a choice. I could curl up in a fetal position and continue to wish I was dead. Or, I could stand up, put one foot in front of the other and keep going and fight back. I rode my bike and I rode it hard. I could feel Jerry with me. I pushed myself to the point of exhaustion, challenging my emotional pain with physical pain. I rode and I cried. (American Heart Association).

One story closer to home about cycling and grief that stood out for me was the one that emerged in 2000 around Scott McGrory and his family. McGrory is the well known former Australian professional cyclist who won the Madison gold medal with Brett Aitken at the Sydney Olympics. Tragically, in the lead up to his Olympic campaign in 2000, McGrory’s 11-week old son passed away from a heart condition.

Speaking in an interview a few years ago, McGrory’s reflections about that time perhaps reveal a positive connection between grief and cycling, but they also remind us that the bike is not a magic pill that works all of the time:

There were times when I felt invincible, drawing strength from what had happened, and a day later I’d be absolutely useless. One day I did a five-hour ride to the Dandenongs and as it started to rain I looked to the heavens and yelled, ‘Bring it on!’ The harder it rained and the windier and colder it got, the better – nothing was going to touch me that day because I was Superman. The next day I got only 20 minutes into the same ride and had to stop on a bridge over the Yarra because I had been crying for several blocks and couldn’t see where I was going.

Cycling Worked for me

Overall, the available evidence suggests that physical activity and exercise like cycling can have a positive impact on mental health, and could be one helpful strategy for some people experiencing grief. However, it is also clear that cycling is unlikely to be a ‘cure all’ for everyone, or for the most severe forms of complicated grief, clinical depression, or other mental health illnesses.

After my father died, cycling has helped me to live with and understand my grief. I had other vital assistance too – my wife, family, relatives, friends, and my father’s friends all played important roles, and I also drew upon professional help.

Mile-for-mile though, I found the simple act of riding a bike was the ‘best’ thing I could do to stay well. The hundreds of hours and thousands of kilometres I spent riding after my father’s death is working for me.

Cycling helped me bring together my physical, emotional, and cognitive energies in a focus on moving towards an understanding of what it really meant to lose my father. I am still learning.

Originally published by The Conversation, 06.22.2016, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.