Beset by the pressures of modern life, you might feel that you ought to reduce your blood pressure, be more present in the moment, optimise your immune system or increase your willpower. Perhaps you even dream of having more intimate sex, enlightening your spirit or enhancing your athletic performance. Many experts would tell you to learn how to breathe properly.

By Effie Webb

Freelance journalist

We take over two billion breaths in our lifetime. Though the vast majority of these are subconscious and taken for granted, throughout history we have sought special ways of breathing to improve health. Breath-centred practices are central to many ancient religions and cultures, while some of the most disparate schools of thought on health and wellness have one feature in common: breathing.

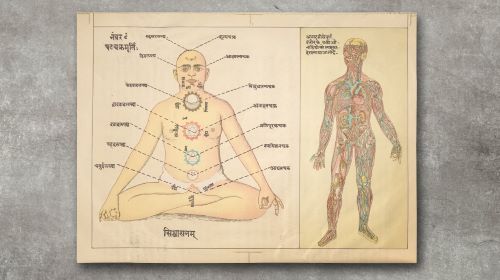

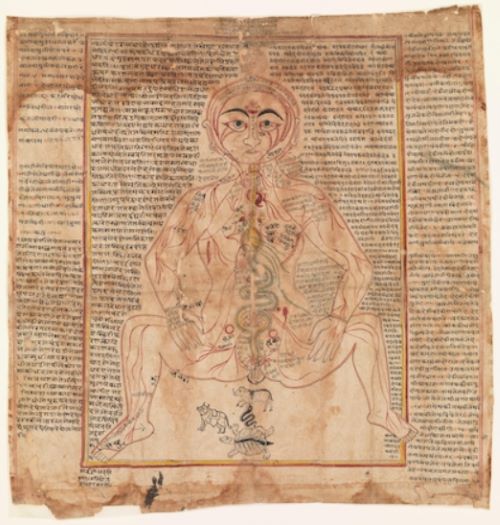

Many therapeutic breathing practices we know today developed from ancient Hindu disciplines. Pranayama, which stems from the Sanskrit prana (life force) and ayama (to draw out or extend), is a yogic practice dating back to roughly sixth-century BCE India.

Alongside simple deep breaths, yogic practitioners teach four main types of pranayama breathing: ujjayi (which roughly translates as “victorious breath” or “ocean breath”) for improved concentration; bhastrika (“energising breath”) to clear the airways; adham pranayama (abdominal breathing) for a stronger immune system; and nadi shodhana (alternate nostril breathing) to reduce stress. Featured in texts like the Bhagavad Gita, pranayama was one of the first instances of the idea that controlling your breathing could help you to live longer, protect against illness and help with healing.

The Sanskrit word ‘tantra’ translates as ‘woven together’.

Ancient breathing techniques were not just for individual bodies. With roots in Hinduism, tantric sex describes slow, meditative sex where the enjoyment of physical sensations at all points along the sexual journey is more important than reaching orgasm. Tantra recommends that partners concentrate on synchronised breathing while maintaining eye contact in order to build a deeper connection and heightened intimacy.

Sexual problems like anorgasmia and erectile dysfunction can also be resolved, tantric practitioners claim. Today, two centuries of changing interpretations have left behind misconceptions about what Tantra is and what it involves. Contrary to popular belief, Tantra is not merely a sexual practice, but rather a spiritual South Asian philosophy that celebrates the body and the self.

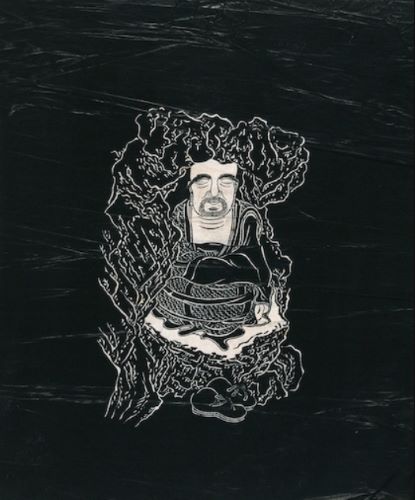

Buddha instructed followers to become aware of their breath during meditation. Lohan, one of Buddha’s disciples, sits meditating with his eyes closed.

Breathing and mindfulness go hand in hand. Ānāpānasati, or “mindfulness of breathing”, is a type of meditation from the Theravada School of Buddhism. Buddha instructed followers to sit beneath a tree in the forest and mindfully observe how the breath flowed through the body. If you become distracted, or your breaths become too long or short, you return your attention to the breath.

Focusing on your breath is supposed to bring you back to the present moment and the full richness of experience it contains. Unlike pranayama, where different combinations of breathing speeds, patterns and bodily postures promise to achieve different ends, people can do ānāpānasati while seated, lying down or walking, without attempts at changing or controlling their breath.

A mastery of meditation can take years, but the benefits reaped from regular practice are rich and varied, Buddhists maintain. Today, breathing and meditation are used in secular ways too. Ānāpānasati features in John Kabat-Zinn’s Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, pro athletes meditate to enhance sporting performance, and schools teach meditation techniques in order to foster better emotional regulation among students and teachers.

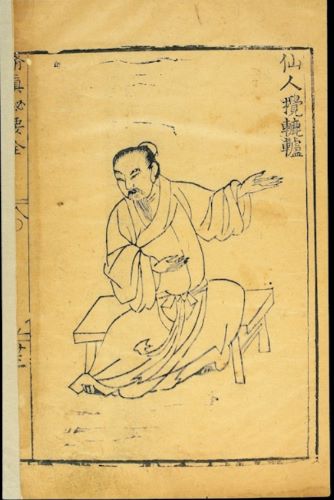

Xianren jiao lulu (“The Immortal turns the pulley”) is a daoyin breathing technique designed to treat upper body pain.

Breathing techniques claim to cure physical disease as well as bolster psychological wellbeing. Daoyin is a movement-based practice, first documented in ancient Chinese medical manuscripts. It combines controlled breathing, slow physical movements and mental focus to direct the flow of qi (the body’s internal energy).

The Daoyin jing lists the six healing breaths (he, si, hu, xu, chui, and xi), each associated with a particular organ and set of ailments. Chui, for example, is the breath connected with the kidneys and ears, which, according to proponents, helps to treat abdominal colds, hearing afflictions and infertility. Meanwhile, hu, ruled by the spleen, supposedly helps with conditions like low fevers and bad circulation.

Unlike pranayamic yoga, which originally formed part of the hermit culture, daoyin practice in China was the domain of the aristocracy and upper classes, undertaken away from ordinary society to alleviate physical discomfort and illness and allow for greater enjoyment of daily luxuries.

Today, daoyin, just like yoga, is cropping up in therapeutic and spiritual contexts in the West, with recent studies highlighting daoyin as instrumental in improving physical performance, lung function and activity tolerance level in COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) sufferers.

The chest of a man with asthma. Dr Konsantin Buteyko prescribed breathing to alleviate asthma symptoms.

Not all therapeutic breathing practices have such old roots. Buteyko breathing, a family of techniques devised to promote slower, deeper and more effective breathing, shares its name with its 20th-century creator, Ukrainian doctor Konstantin Buteyko. While working on an acute respiratory hospital ward in the 1950s, Buteyko noticed that patients with a slower breathing rate were more likely to recover, whereas faster breathing predicted more rapid deterioration.

Buteyko persevered against initial scepticism from the Soviet government, promising that his techniques would help to slash medical costs for an already strained Soviet health budget. Eventually, in the 1980s, Buteyko breathing was accepted as a management system for respiratory conditions like asthma.

A 2012 study found that adult asthmatics who practised Buteyko breathing were better able to control their asthma symptoms than a control group. However, the plausibility of evidence like this is questioned by the medical community, the Australian government finding no clear evidence of its effectiveness in 2015.

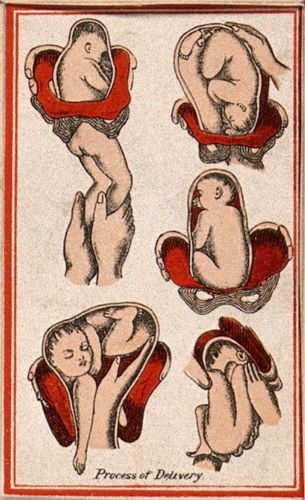

Proponents of natural birth recommend breathing techniques practised before, during and after giving birth.

Breathing has been hailed as a pain-management method to make giving birth more comfortable. Influenced by early advocates of natural birth, Marie Mongan first coined the term ‘hypnobirthing’, a mixture of visualisation, relaxation and deep-breathing techniques, in her 1989 book.

According to Mongan, controlled deep breaths before and during labour help to trigger the parasympathetic nervous system and promote a Zen-like state of mind, which allows for a more relaxed birthing experience. Although research is limited, some studies suggest that hypnobirthing may help mothers to manage pain naturally, while reducing the need for interventions like caesareans.

The experience of childbirth can be as traumatic for babies as it is for mothers.

As well as preparing mothers to give birth, some practitioners claim that breathing can help people process the trauma left over from their own birth and infancy. Rebirthing breathwork was pioneered by psychotherapist and spiritual guru Leonard Orr in the 1960s.

Orr claimed to have relived his own birth by chance while in the bath, and argued that breathwork could be harnessed to purge traumatic childhood memories that had previously been repressed. Orr prescribed instructor-led circular breathing to trigger the release of emotion and the resurfacing of difficult childhood memories.

Despite Orr’s bold claims that rebirthing can help treat PTSD, depression, ADHD and chronic pain, medical research does not support its use, and existing evidence is solely anecdotal. Following the death of a ten-year-old girl, Candace Newmaker, during a rebirthing therapy session in 2001, rebirthing has been banned in her birthplace in North Carolina and in Colorado, where she died.

Johns Hopkins University was the birthplace of research into holotropic breathwork.

Another dubious breathing technique used to mimic powerful experiences is holotropic breathwork. This is the brainchild of psychotherapists and Johns Hopkins University professors Stan and Christina Grof, who were among the first to administer LSD-assisted psychotherapy to help facilitate deep psychological and emotional healing for thousands of patients.

Following the US crackdown on drugs in the 1970s, research into psychedelic interventions largely came to a standstill. The Grofs, intent on searching for a legal alternative, turned their attention to holotropic breathwork, a breathing technique that they claimed induced psychedelic states with a power and intensity comparable to LSD. It involves intense circular breathing, which is essentially controlled hyperventilation, accompanied by up-tempo music to trigger a trance-like state.

However, such rapid and intense shifts in brain chemistry are risky, and hyperventilation can drive fainting, dizziness, spasms and seizures. Evidence that this potentially therapeutic practice is worth the risk is scarce and anecdotal so far, but an ongoing pilot study by Johns Hopkins University is examining holotropic breathwork as a possible treatment for veterans suffering from PTSD.

Breathing techniques have been recommended for veterans suffering from PTSD.

The recognition of breathing as a therapeutic tool for military personnel extends beyond the attainment of ‘psychedelic’ states, with some military clinicians turning away from conventional methods in favour of breath-based ones. A 2014 trial found that Sudarshan Kriya Yoga (SKY), a meditative breathing intervention and form of pranayama, was effective in reducing PTSD symptoms in 11 US veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars.

This very small study may offer hope of an alternative to the generally modest, short-lived success rate of medication and talking therapies for the one in five veterans suffering from PTSD. As it stands, the scarcity of existing evidence is preventing institutions from formally recommending breathing interventions.

Dutch athlete Wim Hof harnesses his breath to break world records. Here he is submerged in a container of ice cubes.

Mental toughness and resilience are among the latest alleged benefits of certain New Age breathing practices. Dutch athlete Wim Hof developed an eponymous method that recommends periods of hyperventilation followed by voluntary breath-holds, which he claims helps users to develop command over mind, breath and body and thus accomplish impressive mental and physical feats.

Hof credits his method as instrumental to his accumulation of over 25 world records: the ‘Iceman’ has withstood nearly two hours inside a container of ice cubes and ran the fastest barefoot half marathon on ice and snow. Icy ventures aside, Hof and other advocates of the technique claim that its health benefits include enhanced immune function, reduced stress, heightened focus and better sleep.

Studies in the Netherlands and US are ongoing to try and scientifically measure the precise effects of the Wim Hof method on mental health, inflammation, neural activity and pain.

The Future of Breathing?

While breath-based practices have been called upon for millennia, some of the more recent formulations may be more harmful than they are healing.

A few are undergoing clinical trials to validate what anecdotal evidence seeks to believe are exciting cures or treatments, and their appeal is clear: breathing practices are, by and large, free of charge, can be used for a lifetime, and offer a range of benefits without pharmaceutical side effects.

It’s encouraging to think that we might alleviate our ills with the power of our own bodies.

Originally published by Wellcome Collection, 06.14.2022, under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.