For medieval cultures, the dying process and death itself was a ‘transition,’ not a rupture.

By Dr. Ashby Kinch

Professor of English

University of Montana

Introduction

In the Halloween season, American culture briefly participates in an ancient tradition of making the world of the dead visible to the living: Children dress as skeletons, teens go to horror movies and adults play the part of ghosts in haunted houses.

But what if the dead played a more active, more participatory role in our daily lives?

It might appear to be a strange question, but as a scholar of late medieval literature and art, I have found compelling evidence from our past that shows how the dead were well-integrated into people’s sense of community.

Ancient Practices

In the medieval period, the dead were considered simply another age group. The blessed dead who were consecrated as saints became part of daily ritual life and were expected to intervene to support the community.

Families offered commemorative prayers to their ancestors, whose names were written in “Books of Hours,” prayer books that guided daily devotion at home. These books included a prayer cycle known as the “Office of the Dead,” which family members could perform to limit the suffering of loved ones after death.

Medieval culture also had its ghosts, which were closely linked with the theological debate concerning purgatory, the space between heaven and hell, where the dead suffered but could be relieved by the prayers of the living. Folk traditions of the dead visiting the living as ghosts were thus explained as souls pleading for the prayerful devotion of the living.

When, How Practices Changed

The Reformation in Europe radically changed this cultural interface with the dead. In particular, the idea of a purgatory was rejected by Protestant theologians.

While ghosts persisted in folk stories and literature, the dead were pushed from the center of religious life. In England, these changes were intensified in the period after Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church in the 1530s. Thereafter, the veneration of saints and commemorative prayers associated with purgatory were banned.

The dead were also removed from view in more literal ways: Reformation iconoclasts, who wished to purge churches of any association with Catholic practices, “whitewashed” hundreds of church interiors to cover the bold, colorful murals that decorated the medieval parish churches.

One of the more popular mural subjects that I have studied for many years was the Dance of Death: over 100 mural paintings of the theme, as well as dozens of manuscript illuminations, have been identified in England, Estonia, France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Switzerland.

A Powerful Metaphor

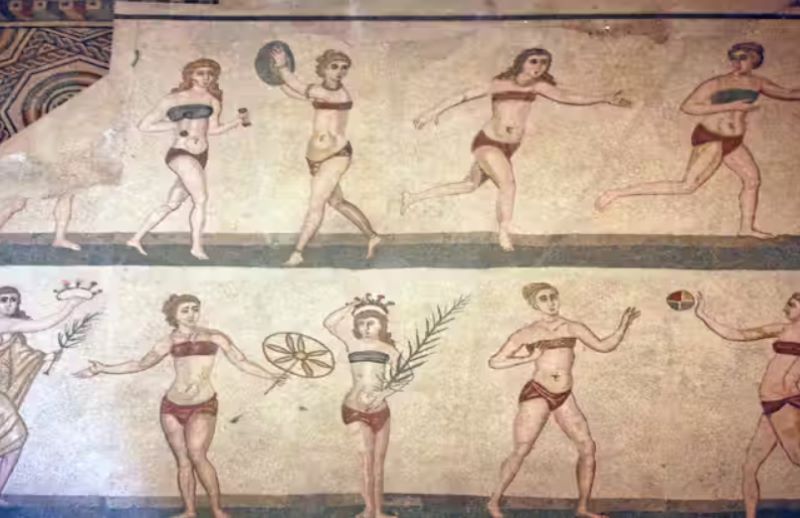

Dance of Death murals typically depicted decaying corpses dancing amid representative figures of late medieval society, ranked highest to lowest: a pope, an emperor, a bishop, a king, a cardinal, a knight and down to a beggar, all ambling diffidently toward their mortal end while the corpses frolic with lithe movements and gestures.

The visual alternation between dead and living created a rhythm of animation and stillness, of white and color, of life and death, evocative of fundamental human culture, founded on this interplay between the living and the dead.

When modern viewers see images like the Dance of Death, they might associate them with certain well-known but frequently misunderstood cataclysms of the European Middle Ages, like the terrible plague that swept through England and came to be known as Black Death.

My research on these images, however, reveals a more subtle and nuanced attitude toward death, beginning with the evident beauty of the murals themselves, which endow the theme with color and vitality.

The image of group dance powerfully evokes the grace and fluidity of a community’s cohesion, symbolized by the linking of hands and bodies in a chain that crosses the barrier between life and death. Dance was a powerful metaphor in medieval culture. The Dance of Death may be responding to medieval folk practices, when people came at night to dance in churchyards, and perhaps to the “dancing mania” recorded in the late 14th century, when people danced furiously until they fell to the ground. But images of dance also provoked a viewer to participate in a “virtual” experience of a community. It depicted a society collectively facing up to human mortality.

A Healthy Community

In analyzing the murals in their broader social context, I found that for medieval cultures, dying was a “transition,” not a rupture, that moved people from the community of the living to the dead in stages.

It was part of a larger spiritual drama that encompassed the family and the broader community. During the dying process, people gathered in groups to aid in a successful transition by offering supportive prayer.

After death, groups prepared the corpse, sewed its shroud and transported the body to a church and then to a cemetery, where the broader community would participate in the rituals. These activities required a high degree of social cohesion to function properly. They were the metaphorical equivalent of dancing with the dead.

The Dance of Death murals thus depicted not a morbid or sick culture but a healthy community collectively facing their common destiny, even as they faced the challenge to renew by replacing the dead with the living.

Many of the murals are irretrievably lost. However, modern restoration work has managed to recover some of them. Perhaps this conservation work can serve as inspiration to recover an older model of death, dying and grief.

Acknowledging the Work of the Dead

In the modern era entire industries have emerged to whisk the dead from view and alter them to look more like the living. Once buried or cremated, the dead play a much smaller role in our social lives.

Could bringing the dead back into a central role in the community offer a healthier perspective on death for contemporary Western cultures?

That process might begin with acknowledging the dead as an ongoing part of our image of community, which is built on the work of the dead who have come before us.

Originally published by The Conversation, 10.29.2017, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.