Courttia Newland’s memories of his mother-in-law’s passing have lost their detail. But a painting has helped him to process the event and his feelings about the flesh and bone of our bodies, and the possibility of something less physical.

By Courttia Newland

Writer

Introduction

My mother-in-law passed away on 9 April 2018. I wasn’t there, but had planned to be, until it became clear that leaving our kids with a close family friend for so long was both unreasonable and impractical. I came home from the hospital sometime around 9 or 10pm, I can’t remember which.

The friend who’d looked after our two kids, her own twins and her older girl since early that afternoon sat in my living room watching an animated movie, the children gathered around the TV in silence. The film was ‘Arthur Christmas’, I think. We snuck off to the kitchen, where I could eat and we could talk. There was plenty of food stacked in the fridge from the weekend and so I ate leftovers and we discussed what happened that night.

My memories then, and even more so now, are muddied, inconsistent with the run of events as they occurred; such is the way with these things. I can’t remember the food, much as I try. Or what I was wearing, or what I said to the children when I came in. I do recall being in tears at one point, but that was fleeting and soon over; I was still hoping for the best.

Our friend, who had recently lost her father to cancer, gave the type of support that only comes from a person who has experienced similar grief. Not to discount the support of others who haven’t, but as someone who’s experienced loss on many occasions, witnessing my wife and her family grieve someone so immediate and important to them has made the difference stark.

But I do consider it strange: the importance of loss weighed against how little remains in my memory. Taste, sound, smell, touch. The senses primary to a writer’s assessment of the world gone, for the most part. Even sight becomes punched through with memory gaps, moments where I wasn’t observing, just being.

The Feeling of Rightness

My mother-in-law, Tara, was in good form just over a week before, on Sunday, when – ah, now I’ve got it – we’d cooked together for my sick wife, side by side at the multi-hob oven. My wife, Sharmila, had been bedridden with flu since Friday. Our daughter, Nyali, fell ill with it a few days before.

I’d thought I’d taken care of them quite well, but when we spoke on the phone, Tara insisted on coming down with Arvind, my father-in-law. He’d take the kids out; she’d cook Sharmila a meal. And so that’s what we did. She made kicheri and curdi and I made chicken curry – perhaps.

I do remember thinking we had pretty much settled, as a family unit; that was a real, vivid thought at the time. We hardly spoke, but the feeling of rightness was more acute than the quantity of words. We chopped garlic and passed spices until pots bubbled and steamed. In silence, we stepped back.

A Mughal courtesan or member of a Mughal royal family looking at a parrot perched on her hand. Gouache painting by an Indian painter. 19th century.

That following Thursday, Tara succumbed to flu-like symptoms. She was driven to A&E the following Monday after she began to slur words and complain of abdominal pains. My wife and I, at home with our friend and a gaggle of kids, raced to the hospital at once. Although Tara spoke when we arrived, she fell into an unconscious state within the hour and died of undiagnosed sepsis only a few hours afterwards.

One moment, here. Another and we are gone. There comes a time when, as children, we face this fully, and rail against it, but what can be done? Nothing at all. If we believe there’s more to us than flesh and bone, that our body is home for something less physical and more incorporeal within, as I do, it’s possible to believe in spirit and the midpoint of its journey – the thing we determine as life. A very un-Wellcome thought, I suspect. It’s inarguable that we inhabit a temporary state in which the essence of who we are will eventually become no more. And yet, perhaps. Perhaps.

Our Questions Become Acute

One of the first things we noted in the chaotic aftermath of Tara’s death were the films she watched in the weeks before. ‘Hotel Salvation’, ‘Piku’, the animated film ‘Coco’. Each a meditation on coming to terms with passing from our present state into death, the possibility of an afterlife and the difficulty of evaluating our own mortality against that which we have lost. Coincidence, or more?

After the last film, viewed in our living room as a part of a Mother’s Day celebration that included lunch for the family, Tara was visibly pleased. “I really enjoyed that,” she said to everyone. Beaming, she told us she’d had a great day.

One moment, here. Another and we are gone.

The Bhagavad Gita teaches, “The soul migrates from body to body. Weapons cannot cleave it, nor fire consume it, nor water drench it, nor wind dry it.” Although Western scientific belief often contradicts aspects of this perspective, our questions become acute when we are in close proximity to death. Where has that person gone? Are they still with us? Can we make contact, however the means?

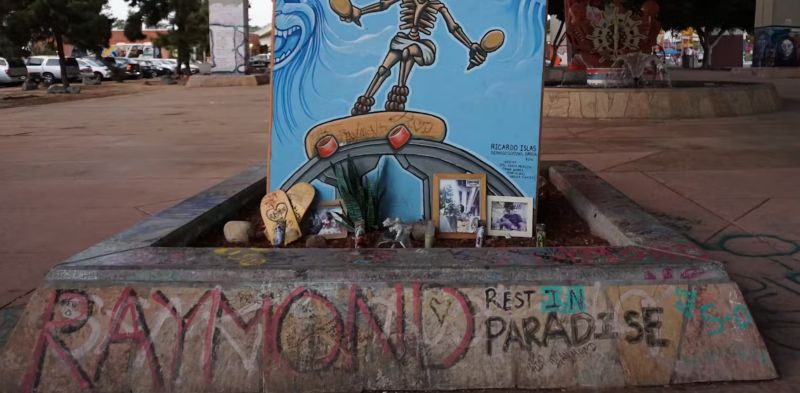

We perform elaborate ceremonies – and by this I include Christian burial and cremation rites – collect and hoard memories, celebrate birthdays when we feel able, visit graves, pour liqueur, raise glasses, keep ashes in vases, or pendants around our necks. We talk of unique personalities, events never to be repeated, words said, food cooked, long-lived jokes and mistakes made.

Never do we deny the existence of the individual, especially if that individual performed gross wrongs. In this, even without meaning to, we uphold our fervent belief in the intermediate life of the human spirit. What came before, we might never know. What comes after, many dispute. But to suggest the here and now is anything other than a stepping stone from one unknown to another is to suggest a form of madness. And so we practise acceptance, again and again.

Originally published by Wellcome Collection, 05.10.2019, under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.