Many in the Western world lack the explicit mourning rituals that help people deal with loss.

By Dr. Daniel Wojcik

Professor, English and Folklore Studies

University of Oregon

By Robert Dobler

Lecturer of Folklore

Indiana University

Introduction

At this time of the year, Mexican and Mexican-American communities observe “Día de los Muertos” (the Day of the Dead), a three-day celebration that welcomes the dead temporarily back into families.

Festivities begin on the evening of Oct. 31 and culminate on Nov. 2. Spirits of the departed are believed to be able to reenter the world of the living for a few brief moments during these days. Altars are created in homes, where photographs and other personal items evocative of the dead are placed. Offerings to the deceased include flowers, incense, images of saints, crucifixes and favorite foods. Family members gather in cemeteries to dine not just among the dead but with them. Similar traditions exist in different cultures with different origins.

As scholars of death and mourning rituals, we believe that Día de los Muertos traditions are most likely connected to feasts observed by the ancient Aztecs. Today, they honor the memory of the dead and celebrate the continuity of generations through loving reunion with those who came before.

As Western societies, particularly the United States, move away from the direct experience of a mourner, the rites and customs of other cultures offer valuable lessons.

Loss of Rituals

Funerals were handled in the home well into the 20th century in the U.S. and throughout Europe. Sometimes, stylized and elaborate public deathbed rituals were organized by the dying person in advance of the death event itself. As French historian Philippe Ariès writes, throughout much of the Western world, such death rituals declined during the 18th and 19th centuries.

What emerged instead was a greater fear of death and the dead body. Medical advances extended control over death as the funeral industry took over management of the dead. Increasingly, death became hidden from public view. No longer familiar, death became threatening and horrific.

Today, as various scholars and morticians have observed, many in American culture lack the explicit mourning rituals that help people deal with loss.

Traditions in Ancient Cultures

In contrast, the mourning traditions of earlier cultures prescribed precise patterns of behavior that facilitated the public expression of grief and provided support for the bereaved. In addition, they emphasized continued maintenance of personal bonds with the dead.

As Ariès explains, during the Middle Ages in Europe, the death event was a public ritual. It involved specific preparations, the presence of family, friends and neighbors, as well as music, food, drinks and games. The social aspect of these customs kept death public and “tame” through the enactment of familiar ceremonies that comforted mourners.

Grief was expressed in an open and unrestrained way that was cathartic and communally shared, very much in contrast with the modern emphasis on controlling one’s emotions and keeping grief private.

In various cultures the outpouring of emotion was not only required but performed ceremonially, in the form of ritualized weeping accompanied by wailing and shrieking. For example, traditions of the “death wail,” which allowed people to cry their grief aloud, have been documented among the ancient Celts. They exist today among various indigenous peoples of Africa, South America, Asia and Australia.

In a similar way, the traditional Irish and Scottish practices of “keening,” or loudly wailing for the dead, were vocal expressions of mourning. These emotional forms of sorrow were a powerful way to give voice to the impact of individual loss on the wider community. Mourning was shared and public.

In fact, since antiquity and throughout parts of Europe until recently, professional female mourners were often hired to perform highly emotive laments at funerals.

Such customs functioned within a larger mourning tradition to separate the deceased from the world of the living and symbolize the transition to the afterlife.

Rituals of Celebration

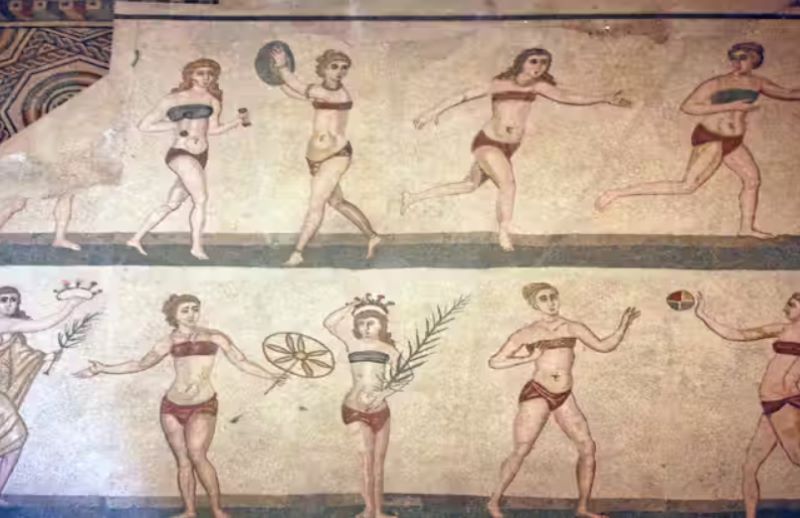

Mourning rituals also celebrated the dead through carnival-like revelry. Among the ancient Greeks and Romans, for example, the deceased were honored with lavish feasts and funeral games.

Such practices continue today in many cultures. In Ethiopia, members of the Dorze ethnic community sing and dance before, during and after funerary rites in communal ceremonies meant to defeat death and avenge the deceased.

In not too distant Tanzania, the burial traditions of the Nyakyusa people initially focus on wailing but then include feasts. They also require that participants dance and flirt at the funeral, confronting death with an affirmation of life.

Similar assertions of life in the midst of death are expressed in the example of the traditional Irish “merry wake,” a mixture of mourning and celebration that honors the deceased. The African-American “jazz funeral” processions in New Orleans also combine sadness and festivity, as the solemn parade for the deceased transforms into dance, music and a party-like atmosphere.

These lively funerals are expressions of sorrow and laughter, communal catharsis and commemoration that honor the life of the departed.

A Way to Deal With Grief

Grief and celebration seem like strange bedfellows at first glance, but both are emotions that overflow. The ritual practices that surround death and mourning as rites of passage help individuals and their communities make sense of loss through a renewed focus on continuity.

By doing things in a culturally defined way – by performing the same acts as ancestors have done – ritual participants engage in venerated traditions to connect with something enduring and eternal. Rituals make boundaries between life and death, the sacred and the profane, memory and experience, permeable. The dead seem less far away and less forgotten. Death itself becomes more natural and familiar.

Funerary festivities such as Day of the Dead create space for this type of contemplation. As we reminisce over our own losses, that is something we could consider.

Originally published by The Conversation, 11.01.2017, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.